Ethical Bystander Intervention

We are all functions of the system that we live in; a system that has taught us how to think about ourselves and others, how to interact with others, and how to understand what is expected of us. These thought processes and expectations are based on the specific set of social identities we were born into that predispose us to unequal roles that allow us to access (or deny access) to resources.

The information here provides a basic overview of important considerations related to Ethical Bystander Intervention. It is crucial that you continue expanding upon this knowledge and look further into the concepts presented that you are unfamiliar with and/or are curious about.

In addition to the resources provided below, you can also review additional terminology interconnected with Ethical Bystander Intervention here.

It is important to note...

The content provided in these guides serve as a starting point for you to begin laying the foundations of your DEIA learning. We highly encourage you to reach out to the office(s)/center(s) listed within each topic to find additional resources, facilitated training opportunities, and learning tools to further your education.

Understanding the Bystander Effect

In March of 1964, 29-year-old Kitty Genovese was stabbed, robbed, sexually assaulted, and murdered near her home in the borough of Queens in New York. Over a dozen people saw the attack, yet no one intervened*. By the time the police were called it was too late. This incident shocked the American public, but also moved several psychologists to try and understand the behavior of people.

Two psychologists, Bibb Latane and John Darley (1968), wanted to explain the phenomenon they called “The Genovese Effect.” Their researched proved bystanders were misled by people around them based on demonstrated pluralistic ignorance (crowd diffusion) or a misread of another’s demeanor. They also found other factors for not intervening such as a person's likeness, prejudice etc.

Note*: There are contradictory accounts related to the number of folks who saw the attack, as well as mentions of folks who intervened but were not successful in their interventions.

A bystander is someone who witnesses or observes acts or situations that create the potential for violence or danger. While they may not be directly involved in the situation, they are present and, in a position, to discourage or prevent an incident of potential violence, harassment and/or discrimination.

The bystander effect, or bystander apathy, is a social psychological phenomenon that refers to cases in which individuals do not offer any means of help to a victim when others are present. The probability of help is inversely related to the number of bystanders.

Ethical bystander intervention refers to safe and positive options that may be carried out by an individual or individuals to prevent harm or intervene when there is a risk of violence.

Ethical bystander intervention includes recognizing situations of potential harm, understanding institutional structures and cultural conditions that facilitate violence, overcoming barriers to intervening, identifying safe and effective intervention options, and taking action to intervene.

There are three determining factors that influence whether or not someone would intervene in a situation.

- Ambiguity: Levels of "sureness," which can vary from situation to situation.

- Cohesiveness: As group cohesiveness increases, so does the likelihood that an intervention will happen.

- Diffusion of Responsibility: The more people around that witness the event, the less likely it is that they will intervene because it is assumed that someone else will do it.

Reasons why people DO NOT intervene...

Believe others think the behavior is okay, they fear for their own safety, they don’t feel qualified to do anything, they think someone else will intervene, they think it’s none of their business, they are in a hurry and don’t have time, or they don’t know what to do to help.

Reasons why people DO intervene...

It’s the right thing to do, their friend is in trouble, they could save someone’s life, or they would want someone to intervene for them.

Did you know?

Bystanders are present in over 60% of all violent crimes but only intervene about 15% of the time.

The Five Cognitive & Behavioral Processes

Within seconds of witnessing an incident (whether it be an easily identifiable emergency or not), your brain is processing enormous amounts of information to determine if you should or should not intervene. These considerations, classified by John Darley and Bibb Latane (1968), are referred to as the five cognitive and behavioral processes of bystander intervention.

Our surroundings influence our reactions and likelihood of intervention.

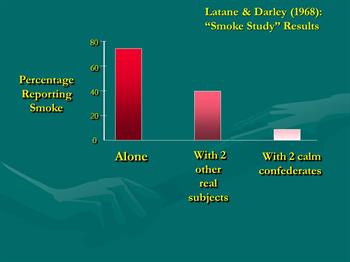

A great example that describes typical responses when exposed to a (potentially) critical situation is with an experiment conducted by two psychologists, Latane and Darley (1968). Latane and Darley demonstrated the impact of social influence using what they called the “Smoke Experiment.”

In the study, participants waited in a room that gradually filled with smoke. The graph above depicts the following results of the study.

Participants were either alone, with a few other participants who were not "in" on the study (unknowing), or with participants who were "in" on the study. Close to 80% of the participants who were in the room alone, reacted and sought help. As additional participants were in the room, the percentage of reactions to the smoke decreased. Overall, the study found that the larger the group, the less likely folks were to intervene. The image above depicts the results of the study.

Once a situation has been noticed, a bystander may be encouraged to intervene if they interpret it as an emergency. As briefly explained in the first process (Notice Something is Going On), interpretations of whether or not a situation is an emergency is based on the principle of "social influence" or "social proof." Bystanders will monitor the reactions of others in an emergency situation to see if others think it is necessary to intervene.

Determinations of personal responsibility felt is dependent upon on three things:

- Is the person deserving of help?

- What is my competence as a bystander?

- What is my relationship to the person being impacted?

There are two forms of assistance:

- Direct Intervention: assisting the victim

- Detour Intervention: reporting an emergency to authorities*

Determining which form of assistance to utilize is assessed based on situational context, social influence etc.

In the next section, we expand upon these two forms of assistance in what we call the 5 D's.

Note*: Some people may not be comfortable or feel safe with the intervention of law enforcement and/or intervention from a person(s)/organization(s) with authority in the space. For many communities and people, the history of mistreatment at the hands of law enforcement has led to fear and mistrust of police interventions.

The following are the considerations one determines before making a decision to act:

- Ambiguity and Consequences

- The more ambiguous a situation is, the less likely people will intervene.

- Bystanders determine their own safety first i.e. if I intervene, will I be at risk?

- Understanding of Environment

- It is important to note that cultural contexts and cultural differences play a critical role; what is safe for you in your environment may not be safe for someone else in that same environment.

- Priming the Bystander Effect

- Being around a group of people can affect a person’s willingness to help i.e. "social influence."

- Cohesiveness and Group Membership

- The closer your group is, the more likely you will intervene.

"We’d all like to consider ourselves helpful people, but are we always quick to lend a hand whenever the opportunity arises?"

SoulPancake, CREDITS:

Executive Producer | Mike Bernstein

Executive Producer | Matt Pittman

Executive Producer | Bayan Joonam

Executive Producer | Shabnam Mogharabi

Director | Zach Wechter

Writer / Host | Julian Huguet

Producer | Hashem Selph

Prod. Coordinator | Tiffany Hutson

Casting Director | Pardis Sullins

DP | Jake Menache

Camera Operator | Fio Occhipinti

Camera Operator | Cory Driskill

1st AC | Jay Janocko

Gaffer | Sam Heesen

Sound Mixer | Eric Bucklin

Production Designer | Michelle Hall

Set Dresser | Valerie Sakmary

Steps for Intervention: The 5 D's*

It is important to remember that we all have our own personality styles and personal comfort levels when it comes to intervention. Please note that the 5 D's do not need to be used in chronological order. We often gravitate more naturally to one of the D's over the others. You can also use multiple D's at once; they tend to have a lot of overlap. If you have additional questions regarding the 5 D's please email us at equitytraining@ucdenver.edu.

Note: 5 D's Model that we use was adapted from Right to Be (previously known as Hollaback!). In 2012, Right to Be partnered with the bystander program Green Dot (who pioneered the Three D’s of bystander intervention) to develop tools to help intervene when you see harassment happen. In 2015, Right to Be expanded those to include “delay,” and in 2017 Right to Be expanded them to include “document.”

Intervene directly* by confronting the individual who is causing harm/harassing someone and notify them of their inappropriateness.

- Be short and direct.

- What you just said made me feel uncomfortable, and here's why...

- Do you realize how problematic what you just said is?

- Are you hearing what I'm hearing?

- I can't be the only one who thinks this is not okay…

Check-in with the person being harassed.

- Are you okay?

- Should I get help?

Note*: Use caution with this intervention tactic. Ensure you and the person being harassed are safe and your engagement will not escalate the harassment.

Create some form of distraction and interrupt the flow of violence. A key with this step is to engage directly with whom is being targeted.

Examples of this can look like spilling a drink or asking for directions.

Empower other allies to become accomplices as active bystanders by asking for assistance, finding a resource, or receiving help from a third party. Do your best to get yourself and the victim into more of a public place. If you observe a situation that appears to be an emergency, or someone's safety is in imminent danger, please call 911.

Examples of this can look like asking someone to join you, utilizing the "fake friend" tactic, or notifying authorities and/or person with authority in the space.*

Note*: Some people may not be comfortable or feel safe with the intervention of law enforcement or person with authority in the space. For some communities, the history of mistreatment at the hands of law enforcement, for example, has led some (people/communities/individuals) to fear and mistrust of police interventions. If it is safe to do so, before notifying authorities, use your distract techniques to see if the impacted party desires this form of intervention. The recommendation is not, "do not call the police." However, it is absolutely critical to understand what contextual dynamics exist that could positively or negatively influence a situation.

Follow up with those impacted. Comfort the person(s) and provide reassurance that it isn’t their fault; accountability is on the person(s) enacting the inappropriate/violent behavior. Be sure to assess when it is safe to check-in with the person experiencing the harm.

Examples of this can look like following up after the fact, making sure they are connected to resources, remaining a visible support system for the person(s), or asking for directions.

Record inappropriate behavior/violence so there is a record available from a third party witness to provide as evidence if necessary. Use this option only if there are folks already assisting the impacted party. If the impacted party is not receiving other assistance, use the other 4 D's first.

Important Considerations:

- Assess your own safety prior to recording.

- Keep a safe distance, film landmarks, state the date and time of the film clearly.

- Hold the camera steady and shoot important shots for at least 10 seconds.

- ALWAYS ask the person (if possible) who was impacted what THEY want to do with the recording.

- NEVER (if possible) post it online or use it without their permission.

Trauma manifests with each of us differently. It is critical to realize that it can be disempowering for someone to have a personal event documented and/or broadcasted. Please be intentional and respectful with any documentation you have and always operate based on the wants/needs of the impacted party.

Importance of Self-Awareness

Bystander behavior is shaped by the social identity relationships to other bystanders, as well as the relationships to folks experiencing the harm and folks enacting the harm. You can make yourself less susceptible to social influences and instead become a more effective support by: (i) understanding/tracking the bystander effect (how it manifests/how it shows up every day for you personally); and (ii) by educating yourself on tactics to navigate the situations and intervene to build a supportive and safe environment.

Resources

Disclaimer

In an effort to assist the University community and the general public, the OE has gathered the list of resources above, including links to websites. Please note, the OE does not accept solicitations to partner, sponsor, promote, and/or publish content from external organizations.

Disclaimer terms regarding published materials:

- The OE is not responsible for the accuracy, legality, or content of the resources above.

- The OE does not endorse any particular resource, product, service, institution, or opinion expressed in the resources, nor does the OE necessarily endorse views expressed or facts presented by the providers or institutions.

- The OE and its employees do not make any warranty, expressed or implied, nor assume any liability for the services provided by any entity, program or resource identified on this site or through links from this site. Further, the OE does not provide any funding to the organizations, programs, and resources identified herein and/or through links. The OE does not provide dedicated funding for these resources.

Acknowledgement

Diversity, equity, inclusion, and access (DEIA) work represents a historical function and is a practicing science. We ask that any redistribution or reproduction of content is credited appropriately to the creators of the content, and if applicable, credited to any scholars or outside resources that were acknowledged and cited in adapted content.

Credit: Sara D. Anderson, Karissa Stolen, and Paulina Venzor, 2020, Office of Equity at the University of Colorado Denver and University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus